The primary objective of this course is to show you that the things you do every day—be it reading, watching television, listening to music, drawing, arguing, watching movies, sleeping can be applied to how you write. I’m just going to show you how. If you already know how, I’m going to show you how to do it better; if you already know how to do it perfectly, I’ll let you write our lesson plans. Really.

During the next two semesters we will be studying works by major British authors and their impact on modern literature and culture. This means that we will be folding the chronology of Brit Lit upon itself—we will look at Nick Hornby’s work alongside Donne’s poetry; punk music alongside classic nonfiction texts and dystopian novels (Brave New World, anyone?); Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Stoppard’s postmodern play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead; Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Brooks’s Young Frankenstein (well, maybe…) and anything else we can mash together.

This course is a survey of British Literature from the present day to the Renaissance, but as you can see from the above outline, it will not be chronological. This presents us with a number of advantages (stronger understanding of intertextuality and impact, immediate understanding of the contemporary relevance of canonical texts, not being stuck in the Middle Ages for an entire “unit”…), as well as one major disadvantage (temporal connections and movements can be de-emphasized). Fear not, noble students: In order to gain an understanding of why Shelley wrote Frankenstein when she did, or why The Clash became popular when they did, we will talk about what was going on in Great Britain when each piece was penned.

In addition to all of this, we will be writing. Often. This will give you the chance to improve your communication skills and interact with the consumables on a deeper level. We will be writing some form of essay once every other week.

You will come away from this course with a solid understanding of British culture and consumables, and a solid grasp on research/writing mechanics. If that's not enough, you will also get all of those Brit Lit allusions in Family Guy and The Simpsons (e.g. Brian: "Does a dog not feel? If you scratch us do our legs not kick?" or even better, from the episode "The King is Dead," when a group of monkeys are writing Shakespeare: "No, they did that on last week's Marlowe").

Fake Schedule

It’s fake because we will never get to all of these works, because we will be sidetracked often, because we will spend lots of time on one section because we really get into it, because we may find better things to read, and because we will not go in this order. You have been warned. But we will listen to The Clash. I’m sorry to have to put my foot down, but The Clash will be listened to and thoroughly enjoyed. Thoroughly. Enjoyed.

The other reason this is a fake reading list is that I am not sure what we should do with it. I have plenty of lessons planned, and a timeline for us to learn the nuts and bolts of writing, but it matters little what we write about. So, I have two guidelines for this section: We all read together, and we write some papers. Oh, and The Clash thing. Other than that, I’m open. Bring stuff in for us all to read (Clean. So help me if it isn’t clean!), watch, draw, listen to, whatever. We will work, but I don’t know what we will be consuming at any one time. Like a little Cracker Jack prize for your junior year. Only you’ll be tested over it. Surprise!

So here it is. If I have left something off, spelled something wrong, given a book the wrong author, etc., let me know. I won’t actually change it, but it would be good to know for the future.

Section One: These are the songs that we sing…

We will begin with this section, but come back to it throughout the year.

Poetry set to music:

| The Beatles: Abbey Road, Revolver, Rubber Soul, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band… | The Rolling Stones |

| The Who’s Tommy | John Lennon (solo) |

| The Clash: London Calling, Black Market Clash | Led Zeppelin |

| Nick Drake | The Smiths |

| Radiohead OK Computer | Coldplay Viva la Vita |

| Portishead Dummy | |

Poetry set to paper:

| A.E. Housman's "To an Athlete Dying Young" | Alfred, Lord Tennyson's "Ulysses" |

| Dylan Thomas | John Donne |

| Lewis Carroll's "Jabberwocky" | Rupert Brooke's "The Soldier" |

| Siegfried Sassoon's "Dreamers" | Stevie Smith's "Not Waving but Drowning" |

| Wilfred Owen's "Dulce et Decorum Est" | Those Big Romantic Six: Coleridge, Keats, Wordsworth, Byron, Blake, Shelley for flava |

| W.H. Auden | T.S. Eliot |

| Winston Churchill "Be Ye Men of Valor" | |

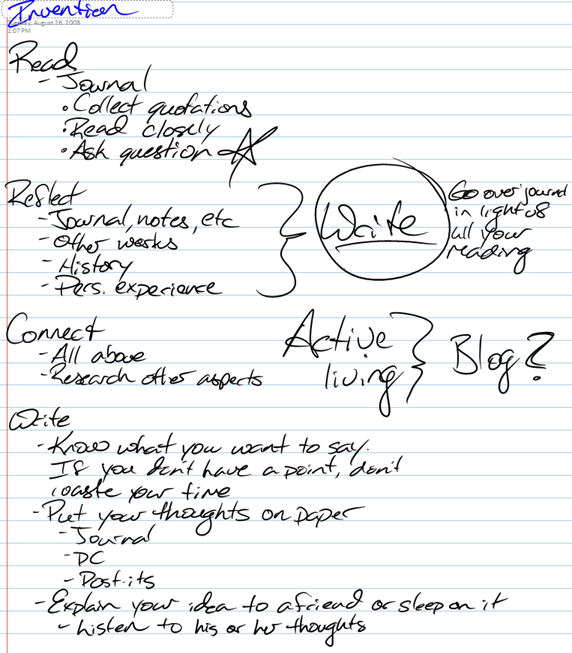

We will begin our reading journals at this point Your journal does not have to be fancy, but I suggest purchasing one with writing space larger than your hand. Carry it with you always; treat it like a friend. You should begin reflecting on the works in your writing—asking questions of the poems, recording personal reactions, making connections with other works. This is a habit you should get into not only because it will make you a better writer (which it will), but it will allow you to talk to your friends and peers more intelligently about things you consume and become more aware of the world around you.

Section Two:

We will make a smooth transition from Donne’s “Meditation #17” and Simon & Garfunkel’s “I am a Rock” (not British, but thematically applicable) into About a Boy by Nick Hornby. You are responsible for purchasing this. If you have trouble making the purchase, let me know as soon as possible and I will take care of it.

About a Boy is a novel about one immature man who meets a 12-year old who is going on 30. In coming together, they learn from one another and grow because of it. In this section, we’ll be discussing maturity, “coolness,” family, friends, and identity. This will be our first major work of length, and there are one or two sections with questionable language, so now is as good a time as any to make the

Classroom Content Disclaimer:

We will be discussing some difficult and sometimes controversial topics in this class. That being said, if you have an objection to anything being presented please do not hesitate to let me know. Talk it over with your parents, ask what they think. I will make the necessary changes to the assignment or provide an alternative work for you to read. The change will be subtle, and no one will be the wiser. If you prefer not to come to me in person (though I would appreciate that), just email me. No worries.

Section Three: Victorian/Edwardian Literature

To shake things up a bit, and give you some control over the next novel you read, we will be covering Victorian/Edwardian literature in groups. Here’s the list:

Charles Dickens’s The Adventures of Oliver Twist (1839)

Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847)

Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights (1847)

George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss (1860)

Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations (1861)

Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871)

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883)

Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Grey (1890)

Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest (1895)

H.G. Wells's The Time Machine (1895)

H.G. Wells’s The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896)

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897)—Flip through this before you choose. It’s better than the movies, but not the same.

H.G. Wells’s War of the Worlds ( 1898)

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902)—More modernist than Victorian, but worth including.

Section Four: Romantic Literature

Back to classroom reading. If you’ve read Frankenstein by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, excellent—we’re reading it again. There is so much to discuss with this work that we could devote an entire session to it. Perhaps we will…

Section Five: Billy Shakespeare’s Pomo-a-go-go

This round will be devoted to Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (1966) and Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1601). Both works are masterfully written, and together make an interesting juxtaposition of English Renaissance and Modern cultures.

Section Six: Dystopian Literature

George Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm

Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World

Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go

William Golding’s Lord of the Flies

Kenzaburo Oe’s Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids

Anthony Burgess’s Clockwork Orange

Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta

Punk music

Section Seven:

Canterbury Tales, "The Wife of Bath's Tale" (around 1390)

Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667)

Jonathan Swift’s “Modest Proposal” (1729) and Gulliver's Travels (1726)

Mary Willstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)

Housekeeping

This could also be called “The Fine Print,” but it is important so I’m keeping it readable. No Charlie and the Chocolate Factory surprise clauses here.

Plagiarism

If you plagiarize, you will fail. There will be no slapping of hands, no talks in the hall. I will certainly give any suspected plagiarist a chance to explain, but I do not see any reason for a student to represent another’s work as his or her own. So, you may be asking yourself, what does he think plagiarism is, exactly? I’m glad you asked.

Plagiarism is taking another’s ideas, words, images, term paper, etc and putting your name on it, without saying, “Hey, this section is by so-and-so.” Quoting from Shakespeare in a paper is not plagiarism as long as you include his name in a citation or works cited page. (We will discuss MLA formatting later in the year.) If you read someone else’s paper, website, book, or the like, and re-write or paraphrase the ideas without telling your reader where you got the idea, that is plagiarism. We will go over plagiarism in more detail later, but the gist of this section is: Do your own work. If you get information or ideas from another source, give them credit. Simple as that. If you have any questions or concerns that a part of your paper might be plagiarized inadvertently, ask me. No one is going to get in trouble for it before the paper is turned in. Again, ask and I will help.

Grades

I will print grade checks often, so there should be no problem with anyone wondering where they are in my class. If you really must know, come by right before school (I get to school at seven every morning) and I’ll tell you your grade.

A large portion of your grade will be based on your participation in class discussions. It is important that you all become comfortable speaking/sharing in class—ideas, insights, things you are currently reading, your best British accent, that sort of thing. The remainder of your semester grade will be divided between various projects, papers, and your final(s). We will work out the percentages for each assignment. I am willing to change any of this if you guys can give me a good reason to do so.

Attendance Policy

Because this is a discussion-heavy class, attendance is very important. If you have more than five unexcused absences (that’s all year, not per semester), I will reduce your grade one letter. All assignments are due the day you get back.